Óðinn

[ˈoːðinː]

ᚢᚦᛁᚾ

Lord of the Hanged

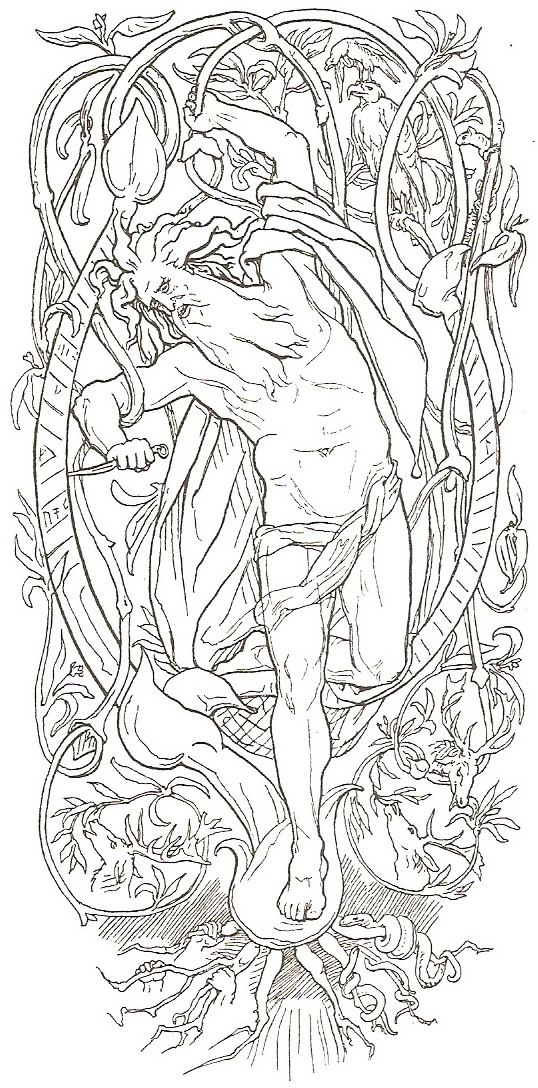

The highest and the oldest of all the gods is Odin. Odin knows many secrets. He gave an eye for wisdom. More than that, for knowledge of runes, and for power, he sacrificed himself to himself. He hung from the world-tree, Yggdrasil, hung there for nine nights. His side was pierced by the point of a spear, which wounded him gravely. The winds clutched at him, buffeted his body as it hung. Nothing did he eat for nine days or nine nights, nothing did he drink. He was alone there, in pain, the light of his life slowly going out. He was cold, in agony, and on the point of death when his sacrifice bore dark fruit: in the ecstasy of his agony he looked down, and the runes were revealed to him. He knew them, and understood them and their power. The rope broke then, and he fell, screaming, from the tree. Now he understood magic. Now the world was his to control. Odin has many names. He is the all-father, the lord of the slain, the gallows god. He is the god of cargoes and of prisoners. He is called Grimnir and Third. He has different names in every country (for he is worshipped in different forms and in many tongues, but it is always Odin they worship). He travels from place to place in disguise, to see the world as people see it. When he walks among us, he does so as a tall man, wearing a cloak and hat. He has two ravens, whom he calls Huginn and Muninn, which mean “thought” and “memory.” These birds fly back and forth across the world, seeking news and bringing Odin all the knowledge of things. They perch on his shoulders and whisper into his ears. When he sits on his high throne at Hlidskjalf, he observes all things, wherever they may be. Nothing can be hidden from him. He brought war into the world: battles are begun by throwing a spear at the hostile army, dedicating the battle and its deaths to Odin. If you survive in battle, it is with Odin’s grace, and if you fall it is because he has betrayed you. If you fall bravely in war the Valkyries, beautiful battle-maidens who collect the souls of the noble dead, will take you and bring you to the hall known as Valhalla. He will be waiting for you in Valhalla, and there you will drink and fight and feast and battle, with Odin as your leader

Ruler of the Æsir

ODIN (Old Norse Óðinn; Old English Woden; Old Saxon Wodan; Old High German Wuotan): The principal deity of the Norse and Germanic pantheon is a cruel and spiteful god, a cynical and misogynistic double-dealer whom the Romans interpreted as being similar to Mercury. He is one-eyed because he offered one of his eyes as a pledge to the giant Mímir in return for access to knowledge. He is old and graying, with a long beard, and has a hat pulled low over his brow. He wears a blue cloak. Etymologically his name means “Fury,” as was noted by Adam of Bremen (“Wodan id est furor”) in his eleventh-century chronicle, History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Odin is the son of the giant Burr (who is the son of Búri and Bestla, Bölþorn’s daughter), and he has two brothers, Vili and Vé. Together Odin and his brothers slay the primordial giant Ymir, whose body becomes the world. Odin’s wife is Frigg, with whom he had a son, Baldr. Thor was born as a result of Odin’s relations with the giantess Jörð, and another son, Váli, came from his liason with the giantess Rindr. In Ásgarðr, Odin lives in Valhöll (Valhalla), seated on his throne, Hliðskjálf, from which he can see the entire world. His attributes are the spear Gungnir, which he casts over the combatants before a battle begins in order to determine who will be victorious; his ring, Draupnir, from which drip eight other similar rings every ninth night; and his horse, Sleipnir, which has eight legs. According to Snorri Sturluson, he also owns the wondrous boat Skíðblaðnir, although this object is usually attributed to Freyr.

Odin is omniscient and knows runes, magic, and poetry. He likes to test his learning against that ofthe giants ( VAFÞRÚÐNIR) and has the power of rendering his foes blind, deaf, and paralyzed ( HERFJÖTURR). He can stop arrows in flight, and he can make his supporters invulnerable. He resuscitates the hanged and other dead men and is the leader of the Wild Hunt (Wodans Jagd, Wuotes her) in all Germanic countries. Odin is adept in the magical technique known as seiðr ( SEIÐR), and he is the master of poetry because he drank the magical mead brewed from the blood of Kvasir. He is also a kind of god-shaman, and his entire character is evidence of the survival of a substantial substratum of shamanistic beliefs. He acquired his powers through a nine-night initiation during which he hung upside down from a windbattered tree. As as result of this he is both a seer and a sorcerer. He can become cataleptic or enter into trance to allow his Double (alter ego) to fare forth and travel the world in the guise of an animal while his body remains lifeless. In the euhemeristic interpretation of Snorri Sturluson’s Ynglinga saga, Odin is an Asiatic king ruling over Ásgarðr, which is located east of the Don River. One time while Odin was away traveling, his two brothers shared his inheritance between them, including his wife, but he took everything back when he returned. He warred against the Vanir. Due to his gift of prophecy, he knew that his descendants would settle in the north. He therefore gave Ásgarðr back to his brothers, Vili and Vé, and set off northward, eventually reaching the sea where he settled first on the island of Odinsey (Odense) and then on the shores of lake Løgrinn (today called Mälaren) in Sigtuna (Signhildsborg, Sweden). A vast number of theophoric place-names provide evidence for both Odin’s importance and his antiquity. The literary texts have also preserved more than 170 names and titles of Odin that are reflective of his deeds and his personality ( GÖNDLIR). His name is also evident in the weekday name Wednesday (which derives from Old English wodnesdæg, “Woden’s Day”)

Lord of the Revenants

Odin is a psychopomp like Mercury as well as a necromancer. He is called “Lord of the Revenants” and “God of the Hanged Men.” He enchanted the severed head of the giant Mímir and regularly consults with it. He is master of the “Hall of the Slain” (Valhöll), where he lives exclusively on wine and gives all his food to the wolves Geri and Freki. The dead men he has selected through his intermediaries, the valkyries, are his fellow inhabitants of Valhalla and are called einherjar, the “elite, single warriors.” He owns two ravens, Huginn and Muninn (“Thought” and “Memory”), who fly out each day and return to report all the news of the world to him, for he has given them the power of speech.

Odin is omniscient and knows runes, magic, and poetry. He likes to test his learning against that ofthe giants ( VAFÞRÚÐNIR) and has the power of rendering his foes blind, deaf, and paralyzed ( HERFJÖTURR). He can stop arrows in flight, and he can make his supporters invulnerable. He resuscitates the hanged and other dead men and is the leader of the Wild Hunt (Wodans Jagd, Wuotes her) in all Germanic countries. Odin is adept in the magical technique known as seiðr ( SEIÐR), and he is the master of poetry because he drank the magical mead brewed from the blood of Kvasir. He is also a kind of god-shaman, and his entire character is evidence of the survival of a substantial substratum of shamanistic beliefs. He acquired his powers through a nine-night initiation during which he hung upside down from a windbattered tree. As as result of this he is both a seer and a sorcerer. He can become cataleptic or enter into trance to allow his Double (alter ego) to fare forth and travel the world in the guise of an animal while his body remains lifeless. In the euhemeristic interpretation of Snorri Sturluson’s Ynglinga saga, Odin is an Asiatic king ruling over Ásgarðr, which is located east of the Don River. One time while Odin was away traveling, his two brothers shared his inheritance between them, including his wife, but he took everything back when he returned. He warred against the Vanir. Due to his gift of prophecy, he knew that his descendants would settle in the north. He therefore gave Ásgarðr back to his brothers, Vili and Vé, and set off northward, eventually reaching the sea where he settled first on the island of Odinsey (Odense) and then on the shores of lake Løgrinn (today called Mälaren) in Sigtuna (Signhildsborg, Sweden). A vast number of theophoric place-names provide evidence for both Odin’s importance and his antiquity. The literary texts have also preserved more than 170 names and titles of Odin that are reflective of his deeds and his personality ( GÖNDLIR). His name is also evident in the weekday name Wednesday (which derives from Old English wodnesdæg, “Woden’s Day”).

In terms of his structural function in the mythology, Odin corresponds to the Mithra-Varuna pair of the Indo-Aryans and to the Roman Jupiter.

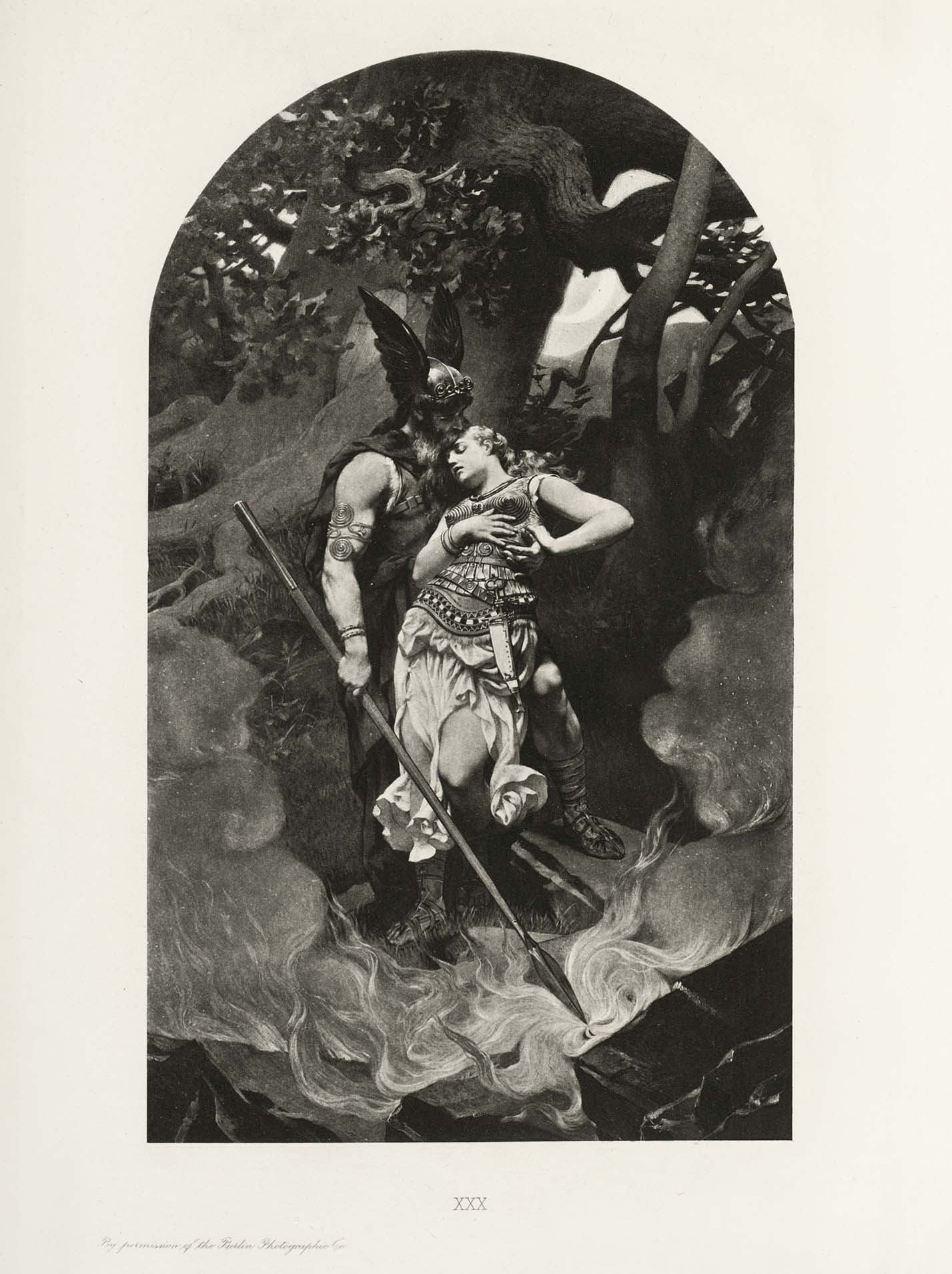

Odin, in his guise as a wanderer, by Georg von Rosen (1886).

Odin's Functions

Odin (Old Norse: Óðinn) is the main god in Norse mythology, while also existing in Germanic mythology as Woden (in Old English), Wodan (in Old Franconian), and Wutan or Wuotan (in Old High German). Described as an immensely wise, one-eyed old man, Odin has by far the most varied characteristics of any of the gods and is not only the man to call upon when war was being prepared but is also the god of poetry, of the dead, of runes, and of magic. Part of the Æsir family of the gods, he helped create the world, resides in Asgard (the stronghold and home of the gods), and gathers slain warriors around him in Valhalla ('hall of the slain'), but is eventually crunched to death by the wolf Fenrir in the Ragnarök, the 'final destiny of the gods' in which the world is destroyed.

Odin is an old, original character in Norse mythology although, as Jens Peter Schjødt points out, many scholars think that his elevated position at the top of the godly hierarchy may be a later addition . Odin’s role of ‘Allfather’ or father of the gods is more of a literary theme from later sources - seemingly influenced by Christian names for God - than an actual reflection of his status in Viking Age societies. Skaldic poetry (Viking Age, pre-Christian poetry mainly heard at courts by kings and their retinues), for instance, names Baldr, Thor, and Vali as Odin’s sons, whereas later on the 13th-century CE Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson also adds Heimdall, Týr, Bragi, Vidarr, and Hodr to the list. Incidentally, despite him being married to Frigg a lot of these sons are from different mothers and Odin appears in many stories as a womaniser, even boasting of his affairs, reminiscent of (and perhaps inspired by?) Zeus from Greek mythology.

ODIN’S MAIN GROUP OF WORSHIPPERS MOSTLY CONSISTED OF THE ELITE - KINGS, CHIEFTAINS & POETS – BUT ALSO INCLUDED WARRIORS. More tangible is Odin’s function as the god of war. Despite his grizzly look he was never actually depicted as a warrior (that, rather, was Thor’s gig) but was called upon when war was being prepared to hand out advice and special gifts. In southern and western Germanic sources, it was Odin who decided whether battles or individual warriors would be victorious or end in slightly less fortunate ways. Odin has his Valkyries - supernatural warrior women - bringing the bodies of fighters slain in battle to his special warrior paradise Valhalla; these fighters are known as the Einherjar and become Odin’s strike-force against the encroaching powers of the Underworld during the Ragnarök. Because of this aspect, individual warriors aare also drawn into Odin's main group of worshippers, which otherwise mostly consisted of the elite: kings, chieftains, and poets.

As his scavenging the battlefields for recruits might give it away, Odin’s connection with war flows naturally into a connection with the dead, which is further illustrated by Odin as the leader of the so-called Wild Hunt – a widespread and old Germanic cult centred around a myth of an army of the dead who ride on the storms. He is also the god of poetry through his knowledge of the runes, as well as of magic (seiðr), even being deemed the most skilled and knowledgeable of all the gods when it comes to this skill. Odin used mainly magic to catch glimpses of the future. As Neil Price explains:

He [Odin] is described as falling into trances, as leaving his body behind and travelling abroad in the spirit-form of an animal, and several times as having visions of wisdom provoked by various kinds of ordeal.

This kind of divination ties in very well with Odin’s role as advisor and would have been of much interest to Viking Age rulers. The nature of Odin’s magic moreover often causes him to be seen as a shaman, an aspect which is further bolstered by his function as a god of healing.

Odin's attributes

Odin can be recognised by his hat and cloak, long beard, and only one eye (reminding somewhat of Gandalf from Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings bar this last aspect). His spear Gungnir is one of his main attributes and seems to have been present in Viking Age belief, as hinted at by miniature spearheads found throughout south and central Sweden.

Some other attributes are the ring Draupnir, which drips to form eight new rings every nine nights, and the horse Sleipnir, which is mentioned early on in Old Norse literature and is set apart by the somehow efficient total of eight legs. Likewise, Odin’s two ravens, Huginn (‘thought’) and Muninn (‘wisdom’) are very old mythical elements already well-established – proven by their appearance on ornaments and rune stones - before c. 800 CE. They fly around the world gathering news, and when they return, they sit on Odin's shoulder and whisper their tidings into his ear. The Prose Edda has Odin say:

Huginn and Muninn hover each day The wide earth over; I fear for Huginn lest he fare not back, - Yet watch I more for Muninn. (Gylfaginning, 38)

Due to this Odin is also known as ‘the raven-god’. If you have ever seen a (movie version of a) battlefield after the action has died down, it becomes clear how Odin’s ravens tie in with his role as god of war and connection with the dead; a battlefield is not just a feast for crows but also a feast for ravens. Other attributes are the Valkyries - who are likely represented by small, female figurines sometimes holding a drinking horn, indicating worship of Odin - and his wolves Geri and Freki. He might also be linked with the eagle and the snake, and his potential function as shaman means the staff is highlighted, too.

Odin's Tales

In line with how shaky our knowledge of Norse mythology as it was in the Viking Age really is, our limited source material only has three gods headlining in more than one known myth; Odin is one of them, alongside Thor and Loki. Most likely, we only have the skeleton of the stories the pre-Christian Vikings would have told and believed about these gods. Some of these bones are as follows:

ODIN’S IMMENSE KNOWLEDGE IS COURTESY OF MÍMIR’S HEAD, WHICH ODIN KEEPS FROM DECAYING SO IT CAN FORWARD SECRET CLUES FROM THE ‘OTHER WORLD’.

Before the creation of the world, Búri, the forefather of the gods, appeared out of the ice, and his son Borr and the giant-daughter Bestla sired Odin and his brothers (usually named Vili and Vé). The brothers then slew the proto-giant Ymir and used his flesh to create the earth, his skull to form the sky, his bones for the mountains, and his blood to make the sea. With an actual residence in place, they then shaped the first human couple, Ask and Embla, out of two trees or pieces of wood.

Odin’s immense knowledge is courtesy of Mímir’s head (or else due to drinking from Mímir’s well). Mímir was a wise advisor about whom Snorri Sturluson reports how the Vanir (the family of fertility gods) chopped off his head and sent it to Odin, who turns to magic and healing herbs to keep the head from decaying so it can forward secret clues from the ‘Other World’. According to Snorri, the price Odin has to pay for this is one of his eyes. His boosted knowledge pops up in a few other myths (known from the Poetic Edda); in the Vafþrúðnismál Odin initiates a battle of wits with the giant Vafþrúðnir and beats him, while in the Grímnismál a disguised Odin is tortured and ends up revealing his extensive mythical knowledge to King Geirroðr.

Furthermore, Snorri explains that Odin’s superb poetic skills are due to him stealing the mead of the skalds (i.e. poets) by sleeping with the giantess Gunnlǫð, guardian of the mead, for three nights. Because of this cosying up to her, he is allowed three sips, but he simply chugs and drains the containers, shape-shifts into an eagle and legs it (well, wings it) out of there. Also connected to poetry, Odin gains knowledge of the runes, too, attributed by the Hávamál poem to a self-sacrifice:

""I know that I hung on a windy tree nine long nights, wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin, myself to myself, on that tree of which no man knows from where its roots run. (Hávamál, 138) .

is relentless pursuit of knowledge is made clear here in the lengths he goes to (very deliberately – he sacrifices himself to himself) in order to unlock the runes; nine nights of swinging from a branch of Yggdrasil, the World Tree, with a spear wound that put him close to death, and only then are the runes revealed to him.

At the Ragnarök, Odin’s wisdom and power are put to the test. Natural catastrophes including a horrible winter, as well as Fenrir devouring the sun, herald the coming of the forces of the Underworld, Heimdall sounds the alarm, Mímir’s head is consulted, and the gods have a huddle underneath Yggdrasil to decide what to do. However well-prepared, though, once the battle erupts Odin bravely takes on Fenrir but meets his end in the creature’s jaws, dying alongside many of his fellow gods who perish to various foes but also slay many in the process.

Odin's Cultus

Belief in Odin was so widespread throughout Germanic regions and parallels between him and the Indian god Varuna so unmistakable that it is likely his origins lie all the way back in the Indo-Germanic tradition. Already in the Bronze Age do Swedish rock carvings depict figures of a god holding a spear, who with some imagination might be linked to Odin, and by at least 500 CE he clearly shows up on a range of ornaments alongside birds and warriors. Viking Age picture stones carry on this trend and depict him riding to Valhalla among other things.

However, when bearing in mind his later status as top dog in Norse mythology, actual tangible evidence of a cult of Odin is quite sparse. Places named after Odin – a decent indicator of cult practices and popularity – are entirely absent in Iceland between its settlement and the coming of Christianity, and very rare in the south of Norway, although they pop up here and there in the south of Sweden and in Denmark. Thor, in contrast, steals all the limelight and is much more visible in a cult context than his father. Luckily, Rudolf Simek has a way to soothe our confusion:

Indeed, it seems likely that the literary sources considered him to have such an elevated position from their own point of view, since there can be no doubt that Odin was the god of poetry (and poets), and our sources, which come either directly or indirectly – via Snorri’s systemization – from the skalds of heathen times not surprisingly show a particular inclination in favour of the god of their own craft. (243)

So, rather than there being an all-encompassing cult of Odin as the main god of Norse mythology, it makes more sense that he was venerated in specific contexts and by specific individuals – mostly poets, warriors, chieftains, and kings. Grisly human sacrifices, for instance, tend to be exclusively dedicated to Odin. Otherwise, in Viking Age belief, he was just one of the gang. This is visually spelled out in the great pagan temple of Old Uppsala in Sweden, too; in 1070 CE Adam of Bremen wrote of his visit to this place that a statue of Thor stood prominently in the centre of the hall, with Odin and Freyr to the side, and that sacrifices were made to Thor in case of famine, to Odin in times of war, and to Freyr for wedding-related activities.

Credits

Please let us know if u have not been credited. We are gratefull to all people bringing this wonderful subject back to us.

References:

The writings of Dr. Jackson Crawford and Daniel Mc Coy are a neverending inspiration and most favoured of sources.Kershaw, The One-eyed God; Régis Boyer, “Óðinn d’après Saxo Grammaticus et les sources norroises: étude comparative,” Beiträge zur nordischen Philologie 15 (1986): 143– 57; Peter Buchholz, “Odin: Celtic and Siberian Affinities of a Germanic Deity,” Mankind Quarterly 24:4 (1984): 427–37; Lotte Motz, “Óðinn’s Vision,” Maal og Minne 1 (1998): 11– 19; Clive Tolley, “Sources for Snorri’s Depiction of Óðinn in Ynglinga Saga: Lappish Shamanism and the Historia Norvegiae,” Maal og Minne 1 (1996): 67–79

Emma Groeneveld