Þórr

/θɔːr/

ᚦᚢᚱ

the brawny thunder god

Midgard's most revered

Thor, Odin’s son, is the thunderer. He is straightforward where his father Odin is cunning, good-natured where his father is devious. Huge he is, and red-bearded, and strong, by far the strongest of all the gods. His might is increased by his belt of strength, Megingjord: when he wears it, his strength is doubled. Thor’s weapon is Mjollnir, a remarkable hammer, forged for him by dwarfs. Its story you will learn. Trolls and frost giants and mountain giants all tremble when they see Mjollnir, for it has killed so many of their brothers and friends. Thor wears iron gloves, which help him to grip the hammer’s shaft. Thor’s mother was Jord, the earth goddess. Thor’s sons are Modi, the angry, and Magni, the strong. Thor’s daughter is Thrud, the powerful. His wife is Sif, of the golden hair. She had a son, Ullr, before she married Thor, and Thor is Ullr’s stepfather. Ullr is a god who hunts with bow and with arrows, and he is the god with skis. Thor is the defender of Asgard and of Midgard. There are many stories about Thor and his adventures. You will encounter some of them here.

The Anti-Cross

Followers of the Norse religion wore the hammer, or cross, of Thor around their necks the same way Christians wear the cross. After Christianity began its invasion of Northern Europe, many of the followers of the old ways began wearing Thor’s hammer as a sort of anti-cross. It was a silent form of protest against the new religion.

Thursday/Donnerstag

Thursday is Sweden’s day of Thor. Thor’s Day was treated similarly to Christianity’s Sunday. No one did any heavy work on this day. This was also the special day of the week for predictions and divinations of all sorts.

The name is derived from Old English Þūnresdæg and Middle English Thuresday (with loss of -n-, first in northern dialects, from influence of Old Norse Þórsdagr) meaning "Thor's Day". It was named after the Norse god of Thunder, Thor.Thunor, Donar (German, Donnerstag) and Thor are derived from the name of the Germanic god of thunder, Thunraz, equivalent to Jupiter in the interpretatio romana.

Since the Roman god Jupiter was identified with Thunor (Norse Thor in northern Europe), most Germanic languages name the day after this god: Torsdag in Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish, Hósdagur/Tórsdagur in Faroese, Donnerstag in German or Donderdag in Dutch. Finnish and Northern Sami, both non-Germanic (Uralic) languages, uses the borrowing "Torstai" and "Duorastat". In the extinct Polabian Slavic language, it was perundan, Perun being the Slavic equivalent of Thor.

A birthday with Blessings

As part of the superstitions surrounding Thor and Thor’s Day, it was believed that people born on Thor’s Day had the ability to see ghosts.

Animal Sacrifice

As part of the superstitions surrounding Thor and Thor’s Day, it was believed that people born on Thor’s Day had the ability to see ghosts.

Oak Groves

Thor was worshipped in oak groves. Because oak trees are mighty and strong like Thor, his worshippers would visit these sacred groves to speak to him and ask for his help.

Idols

Images of Thor were often carved into wood or bone. Sadly, when Christianity took over, these sacred idols were destroyed.

More powerful then Christ

As Christianity was being forced on the people of Denmark, some of them accepted Christ as a god, but felt that he was a weaker god compared to their Thor and Odin. This angered the Christians who then tried to portray the Norse gods as evil spirits.

While Christianity did gain foothold in Northern Europe, the old ways never fully died. Today, the old ways have returned and people are once again calling upon their gods.

The Brute

His courage and sense of duty are unshakeable, and his physical strength is virtually unmatched. He even owns an unnamed belt of strength (Old Norse megingjarðar) that makes his power doubly formidable when he wears the belt. His most famous possession, however, is his hammer, Mjöllnir (“Lightning”). Only rarely does he go anywhere without it. For the heathen Scandinavians, just as thunder was the embodiment of Thor, lightning was the embodiment of his hammer slaying giants as he rode across the sky in his goat-drawn chariot. (Of course, they didn’t believe he physically rode in a chariot drawn by goats – like everything else in Germanic mythology, this is a symbol used to express an invisible reality upon which the material world is perceived to be patterned.)

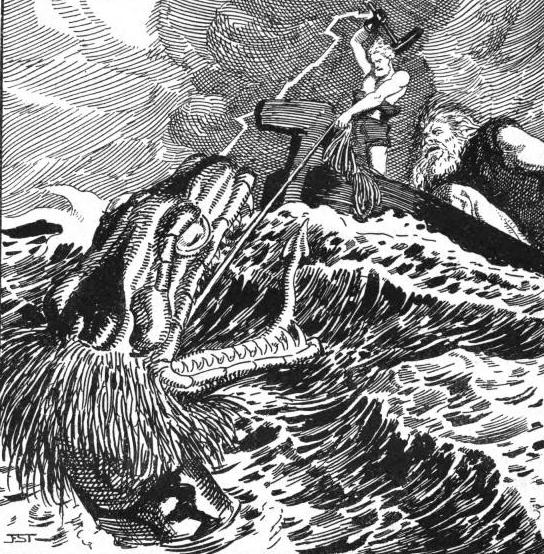

Thor’s particular enemy is Jormungand, the enormous sea serpent who encircles Midgard, the world of human civilization. In one myth, he tries to pull Jormungand out of the ocean while on a fishing trip, and is stopped only when his giant companion cuts the fishing line out of fear. Thor and Jormungand finally face each other during Ragnarok, however, when the two put an end to each other.

Given his ever-vigilant protection of the ordered cosmos of pre-Christian northern Europe against the forces of chaos, destruction, and entropy represented by the giants, it’s somewhat ironic that Thor is himself three-quarters giant. His father, Odin, is half-giant, and his mother, variously named as Jord (Old Norse “Earth”), Hlöðyn, or Fjörgyn, is entirely of giant ancestry. However, such a lineage is very common amongst the gods, and shows how the relationship between the gods and the giants, as tense and full of strife as it is, can’t be reduced to just enmity.

Veneration

Hallowing

His activities on the divine plane were mirrored by his activities on the human plane (Midgard), where he was appealed to by those in need of protection, comfort, and the blessing and hallowing of places, things, and events. Numerous surviving runic inscriptions invoke him to hallow the words and their intended purpose, and it was he who was called upon to hallow weddings. (Evidence of this is preserved, amongst other places, in the tale of Thor Disguised as a Bride.) The earliest Icelandic settlers implored him to hallow their plot of land before they built buildings or planted crops.

Fruits of Land and Men

In addition to his role as a model warrior and defender of the order of society and its ambitions, Thor also played a large role in the promotion of agriculture and fertility (something which has already been suggested by his blessing of the lands in which the first Icelanders settled). This was another extension of his role as a sky god, and one particularly associated with the rain that enables crops to grow. As the eleventh-century German historian Adam of Bremen notes, “Thor, they say, presides over the air, which governs the thunder and lightning, the winds and rains, fair weather and crops.” His seldom-mentioned wife, Sif, is noted for her golden hair above all else, which is surely a symbol for fields of grain. Their marriage is therefore an instance of what historians of religion call a “hierogamy” (divine marriage), which, particularly among Indo-European peoples, generally takes place between a sky god and an earth goddess. The fruitfulness of the land and the concomitant prosperity of the people is a result of the sexual union of sky and earth.

Social Role

In the tales, Loki is portrayed as a scheming coward who cares only for shallow pleasures and self-preservation. He’s by turns playful, malicious, and helpful, but he’s always irreverent and nihilistic.

Trifuncionality

based on the view of GEORGES DUMÉZIL

For Dumézil, “The Indo-European vision of a smoothly functioning world required an ‘organization’ in which the representatives of the first function commanded, the second fought for and defended the community, and the third (the greatest number of them) worked and were productive. In their eyes, it was in this hierarchy that one found the harmony necessary to the proper functioning of the cosmos, as well as that of the society. It’s an Indo-European version of the ‘social contract.’”

Although a similar social organization can be found in various non-Indo-European societies, what makes the Indo-European concept distinct is just how foundational and pervasive it was in their worldview, theology, cosmology, mythology, and political philosophy. It touched every aspect of their way of life and their outlook on life.

The first function is that of sovereignty, and corresponds to the highest social class – that of rulers, priests, and legal specialists. This function is divided into two aspects, one “magical” and the other “juridical.” The former “consists of the mysterious administration, the ‘magic’ of the universe, the general ordering of the cosmos. This is a ‘disquieting’ aspect, terrifying from certain perspectives. The other aspect is more reassuring, more oriented to the human world. It is the ‘juridical’ part of the sovereign function.”

The Indo-Europeans’ gods of the first function tend to include one god who falls into each of these two categories. One is a “magician-creator” who rules “by virtue of [his] creative violence,” while the other is a “jurist-organizer” who rules “by virtue of [his] organizing wisdom.” The two types of sovereign gods form an “antithesis,” but complement one another rather than being in conflict.

The second function “carries the trait of physical force in all its manifestations, from energy, to heroism, to courage.” Its “insatiable champions… vanquish demons and save the universe.” In human society, the second function is the class of warriors, who carry out the orders of the first class and fight on behalf of their people. The gods of the second function are warriors whose intellectual abilities are inferior to those of the first, but who possess the necessary strength to actually put the decisions of the intellectual gods into action.

The third function “is the generative function. It is the domain of the healers, of youth, of luxury, of fecundity, of prosperity; also the domain of the healing gods, the patron deities of goods, of opulence – and also of the ‘people,’ as opposed to the small number of warriors and kings.”The third function’s human social class consists of the farmers, herders, and other “common people” engaged in productive physical labor, who provide the goods necessary for the sustenance of themselves and of the rest of society. Its gods are those who preside over fertility, abundance, and peace. They tend to be simple but wealthy and fun-loving.

The protector

Through archaeological evidence, the veneration of Thor can be traced back as far as the Bronze Age, and his cult has gone through numerous permutations across time and space. One of the features that remained constant from the Bronze Age up through the Viking Age, however, is Thor’s role as the principal deity of the second class or “function”

Thor seems to have always had close ties to the third function as well as the second, and during the Viking Age, a time of great social confusion and innovation, this connection with the third function seems to have been strengthened still more. This made him the foremost god of the common people in Scandinavia and the viking colonies.

This role can be made clearer by contrasting Thor with the god who was virtually his functional opposite: Odin. Odin was the foremost deity appealed to by rulers, outcasts, and “elite” persons of every sort. Odin’s primary values are quite rarefied: ecstasy, knowledge, magical power, and creative agency. They stand in stark contrast to Thor’s more homely virtues. The Eddas and sagas portray the relationship between the two gods as being often uneasy as a result. At one point, Odin taunts Thor: “Odin’s are the nobles who fall in battle, but Thor’s are the thralls.” In another episode, Odin is conferring blessings upon a favored hero of his, Starkaðr, and each blessing is matched by a curse from Thor. In the most telling example, Odin grants Starkaðr the favor of the nobility and rulers, while Thor declares that he will always be scorned by the commoners

Overshadowing Odin and Tyr.

Due to demographic shifts, whereby the second and third functions became largely indistinguishable from one another, the prominence of Thor seems to have increased at the expense of Odin throughout the Viking Age (c. 793-1000 CE). Late period sources describe Thor as the foremost of all the Aesir, a statement that would have been rather ludicrous before the Viking Age, when Odin and his Anglo-Saxon and continental equivalents occupied this position.

Nowhere was this trend more pronounced than in Iceland, which was originally settled in the ninth century by farming colonists fleeing what they found to be the oppressive and arbitrary rule of an Odin-worshiping Norwegian king. The sagas are rife with examples of the fervent veneration of Thor amongst the Icelanders, and in the Landnámabók, the Icelandic “Book of Settlements,” roughly a quarter of the four thousand people mentioned in the narrative have Thor’s name or a clear allusion to him somewhere in their own names. Famed Old Norse scholar E.O.G. Turville-Petre admirably summarizes: “In these [late Viking Age Icelandic] sources Thor appears not only as the chief god of the settlers but also as patron and guardian of the settlement itself, of its stability and law.”

There’s yet another reason for the upsurge in the worship of Thor during the Viking Age. When Christianity first reached Scandinavia and the viking colonies, the people tolerated the cult of the new god just like they tolerated the cult of any other god. However, when it became clear that the Christians had no intention of extending this same tolerance to those who continued to adhere to the worship of the old gods, but instead wanted to eradicate the traditional religion of northern Europe and its accompanying way of life and replace it with a foreign religion, the northern Europeans retaliated. And who better to defend their traditional way of life and worldview from hostile, invading forces than Thor? One of the many areas of life in which this struggle manifested – and one of the easiest to trace by the methods of modern anthropology – was modes of dress. In deliberate contrast to the cross amulets that the Christians wore around their necks, those who continued to follow the old ways started to wear miniature Thor’s hammers around their necks. Archaeological discoveries of these hammer pendants are concentrated in precisely the areas where Christian influence was the most pronounced. Though ultimately doomed, their efforts to preserve their ancestral traditions no doubt benefited from the divine patron whom they could look to as a model.

Famous tales

The Forging of Mjolnir

Loki stirs up mischief among the dwarves and almost loses his head, but ultimately gives the gods several priceless gifts, including Thor’s mighty hammer.

The Fishing of Jormungand

Thor tries to pull his arch enemy, the “world serpent,” out of the depths of the ocean.

The retrieving of Mjolnir

Thor loses his hammer to the giants, and has to go through a humiliating ordeal in order to get it back.

Thor’s duel with Hrungnir

Thor duels with one of the most formidable giants.

The Tale of Utgarda-Loki

Thor and Loki travel to the land of the giants and engage their hosts in a series of contests.

Credits

Please let us know if u have not been credited. We are gratefull to all people bringing this wonderful subject back to us.

References:

The writings of Dr. Jackson Crawford and Daniel Mc Coy are a neverending inspiration and most favoured of sources. the blog of Dr. Karl E. H. SeigfriedNorse-mythology.org

English editions: Saxo Grammaticus, The History of the Danes, Books I–IX, ed. and trans. Hilda Ellis Davidson and Peter Fisher. Latin text and English translation: Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum: The History of the Danes, ed. Karsten Friis-Jensen, trans. Peter Fisher. Cf. also Georges Dumézil, From Myth to Fiction: The Saga of Hadingus, trans. Derek Coltman.

References: [1] Sturluson, “Gylfaginning,” 55. ↩ [2] Saxo Grammaticus. 1905. The History of the Danes. Book VIII. [3] Turville-Petre, E.O.G. 1964. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. p. 138.